Key Points

- Three years since returning to power, the Taliban continues to exert pressure on media in Afghanistan.

- Some media outlets are operating in exile with safeguards to protect reporters on the ground.

- The country ranks 178th out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index.

The journalists file in secret, under codenames.

While some reporters might be living in the same Afghan town or city, their identities remain secret even from each other.

They work for Hasht e Subh, also known as 8am Media.

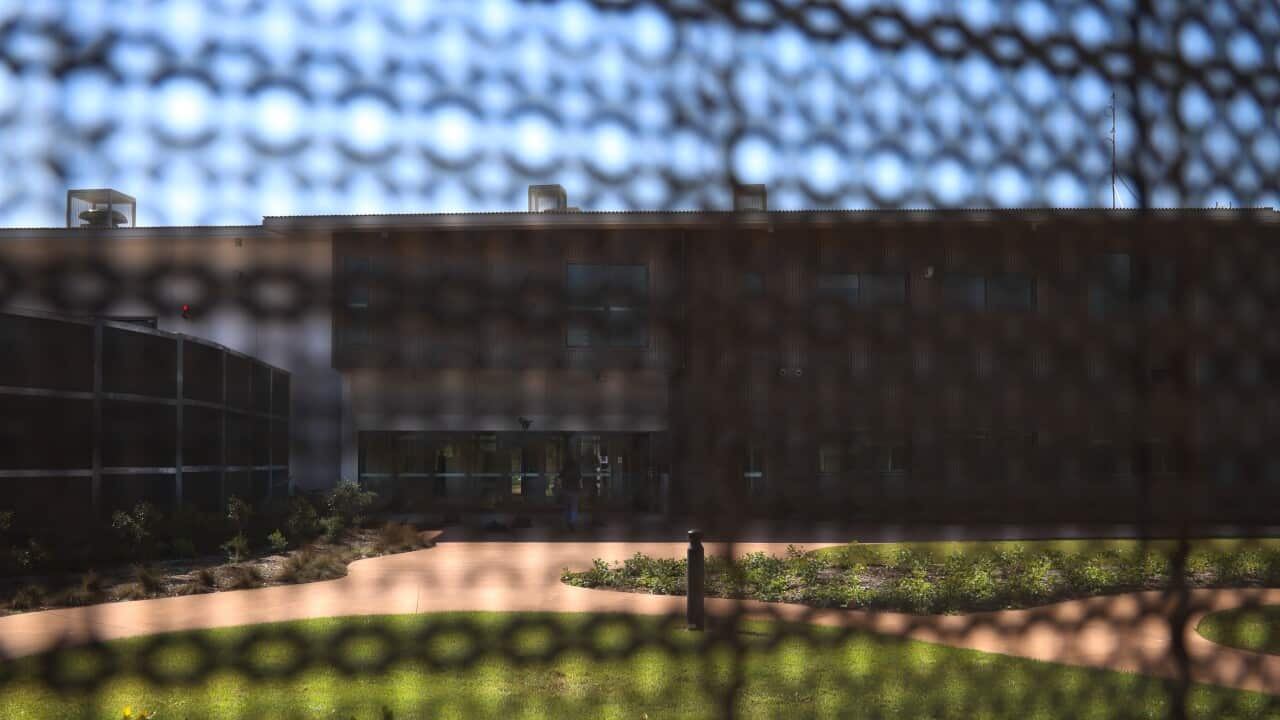

It was once one of Afghanistan’s major newspapers but now it’s operating online and in exile.

The risks for reporters, if they are discovered, are immense.

“We have cases that once a journalist is arrested and just for working for a media outlet that operates from exile, from outside, then they’re tortured,” the executive director of Hasht e Subh, Parwiz Kawa, told SBS World News.

In some cases, they are put in prison, and we also have cases of journalists being disappeared.

Parwiz Kawa

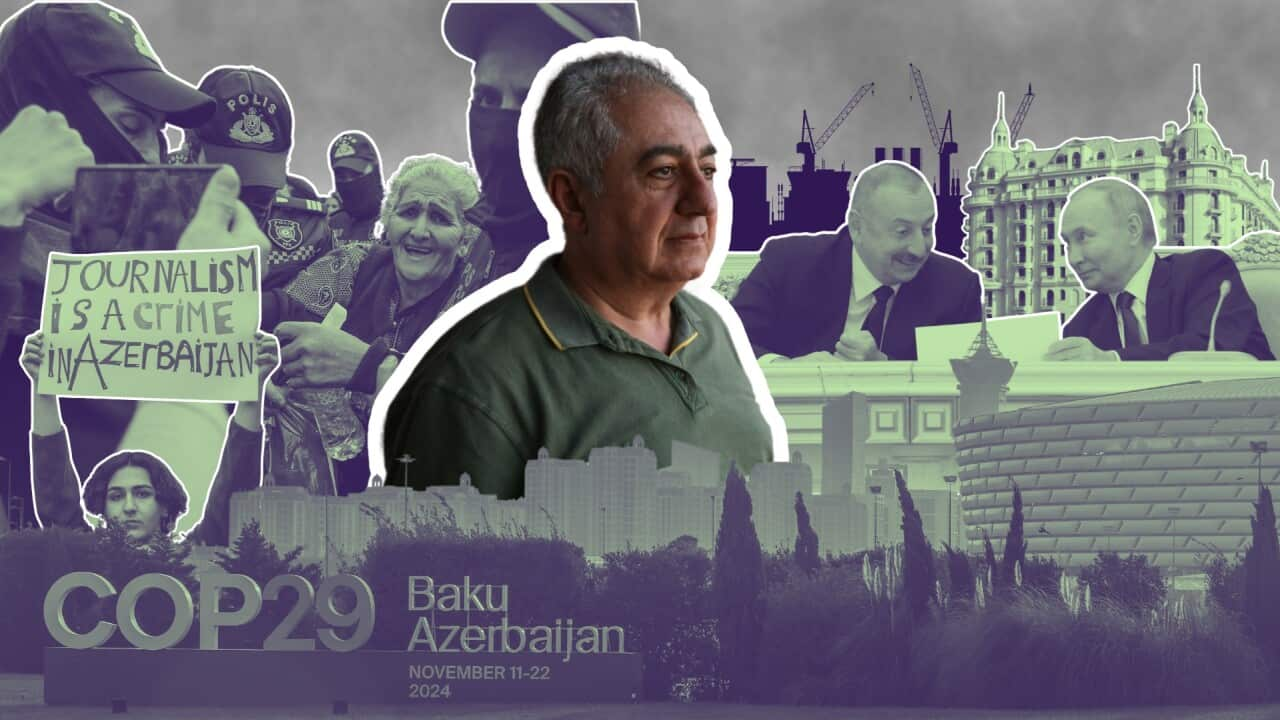

He is now in Canada, helping to keep the news outlet alive along with other editorial staff overseas.

While the website is prohibited under the Taliban, inside Afghanistan its stories are still being distributed through social media or can be accessed if people have a VPN service to get around the ban.

“It’s a bit tricky, we know, and we are thankful to our staff on the ground. We know they file each report with a lot of risks and then send it to our editors. We have a group of editors who are outside the country, and they are processing that, and then it gets translated in various languages and published,” Kawa said.

“In some cases we have two reporters in one place, just to cross-check and verify information. But they don’t know each other. We are just trying to build this mechanism to safeguard them, to protect them, because we know if one is arrested, it might jeopardise the security and the safety of all other staff.”

Exodus of journalists

Channels like TOLO News are still broadcasting under the restrictions of the strict regime, but a reported two-thirds of the journalists who once worked in the country have left the profession and many have fled overseas.

Hundreds of other media outlets have been forced to close.

In the latest case, the Taliban administration suspended 14 media outlets in Nangarhar province, according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists.

Since the Taliban takeover on 15 August 2021, nearly 50 per cent of media outlets in Afghanistan have ceased their operations, while an estimated 90 per cent of women journalists have lost their jobs, UNESCO has .

A member of Taliban security force keeps a vigil during an event organised to mark the ‘World Press Freedom Day’ at the office of the Afghan Independent Journalists Association (AIJA) in Kabul on May 3, 2023. Source: AFP / WAKIL KOHSAR/AFP via Getty Images

On the third anniversary of the fall of Kabul, Hasht e Subh has published stories about the rise of anti-Taliban forces, the crisis of women’s rights in the country and the expansion of the regime’s religious schools.

Afghanistan currently ranks 178th out of 180 in the World Press Freedom Index, down from 122nd in 2021, just prior to the Taliban takeover.

“The Taliban takeover of this country of 40 million people sounded the death knell for press freedom and the safety of journalists, particularly women journalists,” said.

‘Institutionalised censorship’

Mirwais Haidari, an Afghan journalist who worked with various media outlets for 14 years, recently came to Australia on a humanitarian visa.

Now living in Sydney, Haidari told SBS Dari that he originally had no intention of leaving Afghanistan.

He said he continued to work as a journalist after the fall of Afghanistan, but was soon pressured by the Taliban.

“After the fall, when I went to the office and wanted to start my TV show, I noticed that one official was standing in the control room and the other was standing in the studio.

“They dictated me to conduct the interview according to their wishes and they controlled everything,” Haidari said.

Mirwais Haidari is an Afghan journalist and TV presenter now living in Australia. Credit: Supplied/Mirwais Haidari

“Four days later, another group of Taliban officials stormed our office again, gave me written questions and told me to tell the people that the Islamic Emirate group are good, that people should not be afraid, they are not terrorists and have come for the safety of the people.”

According to Haidari, the Taliban intelligence agency then intervened and imprisoned him for a week.

“I was under the control of the 40th (intelligence department) for almost a week. I was pressured and tortured. The torturing continued and they forced me to do whatever the Islamic Emirate said.”

Haidari said the experience took a serious toll.

“My shoulder suffered a serious injury, it has not fully recovered yet and I am still undergoing treatment. There are some other issues that I cannot say.”

Mujeeb Rahman Awrang worked as a journalist in Afghanistan for six years.

He said he was forced to leave the country under Taliban pressure and is currently living in Pakistan.

“The Taliban agencies, especially the intelligence and the Amr-e-Ma’roof (Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice), always put pressure on journalists and try to institutionalise censorship,” he said.

This story was produced in collaboration with SBS News, SBS Pashto and SBS Dari.