As the numbers of children in detention in the Northern Territory continue to swell, medical and legal experts are calling on the government to halt the transfer of Aboriginal kids from facilities in Alice Springs to Darwin.

The Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance NT (AMSANT) says community-based, culturally safe alternatives need to be prioritised.

AMSANT says permanently relocating young people 1500km from their communities, family support, and essential health and cultural services risks causing unnecessary and long-term harm to their wellbeing – without addressing the underlying issues of community safety and the need for improved justice responses.

But the Country Liberal Party government seems unlikely to back off from its hardline stance against children, after Corrections Minister Gerard Maley said in a statement that the previous Labor government had “focused too heavily on the therapeutic model” and that it was time to “ensure offenders know there is a consequence for their actions”.

Since being elected in late August, the CLP, under Chief Minister Lia Finocchiaro, made lowering the age of criminal responsibility to 10 one of its first orders of business – against expert advice from medical, legal, psychological and human rights groups.

The United Nations recommends that the minimum age of criminal responsibility should be 14 and in 2019 specifically singled out , recommending that the federal government legislate to bring the country into line with its obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The CLP government pushed changes to bail and weapons laws through parliament in October, which extend police powers to search and seize weapons from anyone over the age of 10 and give all violent offenders a presumption against bail.

AMSANT chief executive Dr John Paterson said evidence shows that taking young people away from their families, Country and culture negatively impacts their health and wellbeing, and increases the risks of mental health challenges, future reoffending, and further marginalisation and stigma in the community.

“Shifting our young people from facility to facility is not the answer – and will instead only serve to cause more harm,” he said.

“Our young people do not belong in detention and are not problems to be sent away.

“We need to keep young people connected to their communities and we need to see real investment in community-led action and programs, and culturally secure solutions, that genuinely work to address underlying issues and support young people’s futures.”

Blak kids overrepresented in detention

has not updated the statistics about children in detention for almost three months.

But for July and August, the last figures available, Aboriginal young people made up between 98 and 100 per cent of children in detention, despite making up less than 50 per cent of the population in the NT.

Young people held in detention are often unsentenced but have been remanded to custody to await a hearing – of which less than 25 per cent result in custodial sentencing.

“Whether you look at health, crime or any other area where there is a gap between outcomes for First Nations people and the rest of the community, the drivers are the same,” Dr Paterson said.

“Putting our young people in institutional settings entrenches disadvantage, furthering the impacts of intergenerational trauma and harm and perpetuating cycles that are shown to make future offending more likely, to the detriment of the wellbeing of our young people and the wellbeing of our communities.”

For decades, numerous inquiries, including the NT Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children, have recommended that governments across the country replace punitive youth detention facilities with safe, rehabilitative, and community-based options and raise the age of criminal responsibility.

“Keeping young people close to family and culturally safe support networks is critical to their long-term wellbeing and positive future outcomes,” Dr Paterson said.

“Many young people held in these settings have complex health needs, including mental health issues, neurodevelopmental conditions, and substance dependence, which cannot be adequately managed in a centralised detention environment.

“Transfers disrupt the ability for services to continue to provide culturally appropriate continuity of care – increasing the likelihood of negative health outcomes.”

Last week the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA) also called on the NT Government to do more to keep Aboriginal children out of jails and watchhouses.

And respected Larrakia Elder Dr Richard Fejo quit his role as chair of the Darwin Waterfront in disgust at the government’s haste to criminalise kids as young as 10.

NAAJA said in a statement that 10 year old children do not belong in jail.

Seven years ago the Don Dale Royal Commission reported that the NT’s youth detention centres were not fit for accommodating, let alone rehabilitating, children and young people and that the poor conditions created the potential for harm.

“The youth justice and corrections system in the NT is already at breaking point and the legislative changes … will only put more pressure on the system and see children put at risk,” NAAJA said.

NAAJA said their young clients who are not released on bail while awaiting an outcome of their matter are being kept on remand for an average of 137 days (197 days for children under 14) and only 23 per cent are ultimately sentenced to a term of detention.

Since 2021, four NAAJA clients under the age of 14 spent more than 250 days on remand before having the charges against them withdrawn or dismissed.

“At the core of the problem is continuing poverty, disadvantage, trauma and homelessness in Aboriginal communities as well as embedded institutional racism and a ‘tough on crime’ response by authorities,” they said.

“The new legislation … does nothing to address these underlying issues and are targeted to Aboriginal people.”

Natalie Hunter, one of the founders of NAAJA and a senior Nygina and Jabba Jabba woman, said kids don’t belong in jail, they belong on Country with their family.

“Some of our kids are being moved away from family, community and culture … ,” she said.

“Stop taking our kids away.

Our children need health and support, tender loving care and not treated with torture and abuse.

NAAJA says there was no public consultation or committee consideration regarding the tough new laws, which it claims were rushed through without thinking through the consequences, including overcrowding of detention facilities.

“There should have been a joint approach between the government and Aboriginal organisations before the legislation was introduced to improve outcomes around youth incarceration,” the legal service said.

“The lack of information about the legislation and the speed of its passage has caused confusion about the law and is likely to lead to unwarranted and unnecessary interactions with the police and the justice system.”

AMSANT, NAAJA and other advocacy groups are calling for smarter, health-oriented solutions that divert young people away from detention and support their long-term rehabilitation, saying policy should prioritise the physical, emotional, and social health of young people, rather than focus on punitive detention practices.

“We need to push for fundamental change to the way we do justice in the Territory,” Dr Paterson said.

“This means more investment and greater commitment to local, health-driven, and culturally safe solutions that genuinely support young people.”

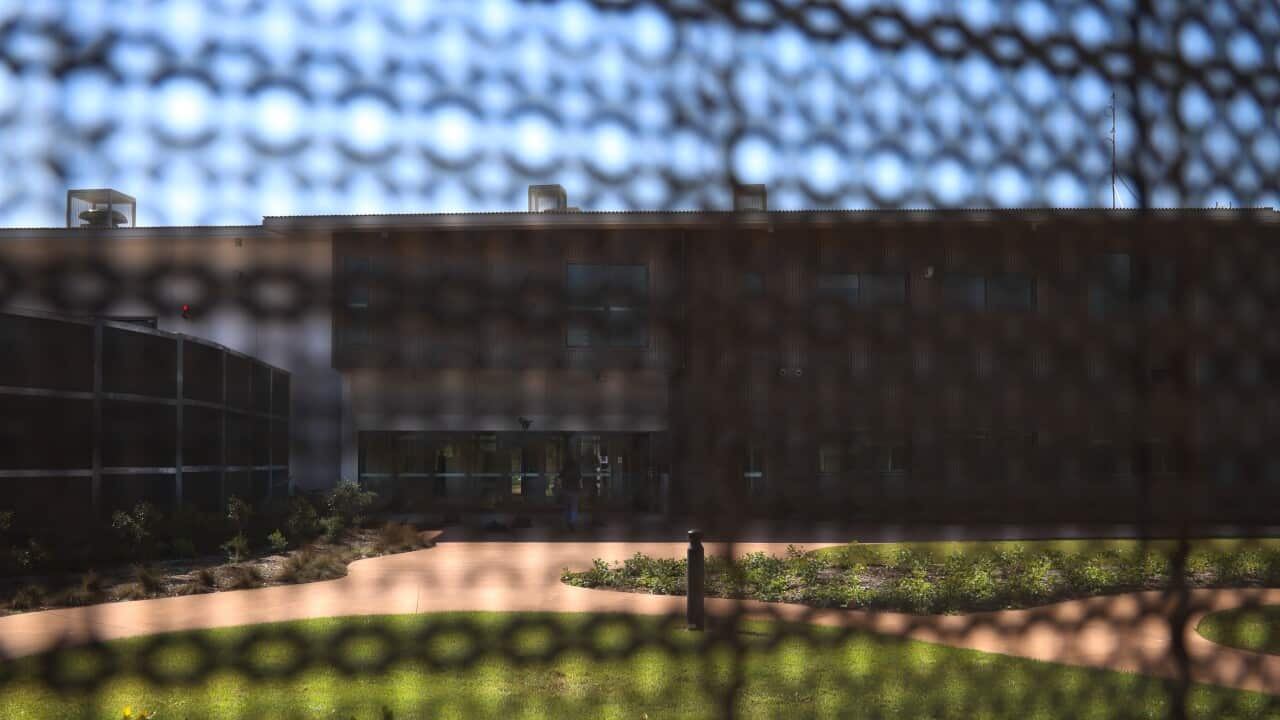

Last week all children in detention in Darwin were transferred from the notorious Don Dale facility to the new Holtze Youth Detention Centre.

During its first week of operation six children aged between 13 and 17 damaged seven bedrooms, with an estimated bill close to $200,000 Corrections Minister Gerard Maley said in a statement.

“Our government will not dismiss this as wear and tear; it is calculated destruction,” he said.

“Damage includes smashed wash basins, metal intercom panels torn from bedroom walls, and metal plate light and power sockets ripped from walls, leaving live wires exposed.”

The new Holtze youth detention facility in Darwin was damaged days after taking in its first children.

NITV understands repairs have been completed.

Mr Maley said two children at the Alice Springs Youth Detention Centre who assaulted youth justice officers and have been transferred to Holtze so far, but the plan is to move all children to the one facility.

“For too long, the previous Labor government put ideology ahead of victims and public safety,” he said.

“… Labor focused too heavily on the therapeutic model and not enough on the safety and security of staff and youth detainees.

“Now is the time to redirect those priorities and ensure offenders know there is a consequence for their actions.”

Mr Maley said in a statement to NITV that young people in detention participate in a structured day program that includes daily routines focused on education and the development of life skills, including programs that support social and emotional and wellbeing.

“While in the centres, youth are also connected to disability and other supports they will continue to access after they leave,” he said.

“Young people require extensive ongoing support in their post-release life, including for ongoing rehabilitation, accommodation, employment, education, training, healthcare, disability support, and connection with community.

“Ongoing supports and continuity of relationships help to prevent young people returning to unhealthy patterns of behaviour or offending.”

According to a report into by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, released this month, 90 per cent of children aged 10-12 at first sentenced supervision order return at some point.

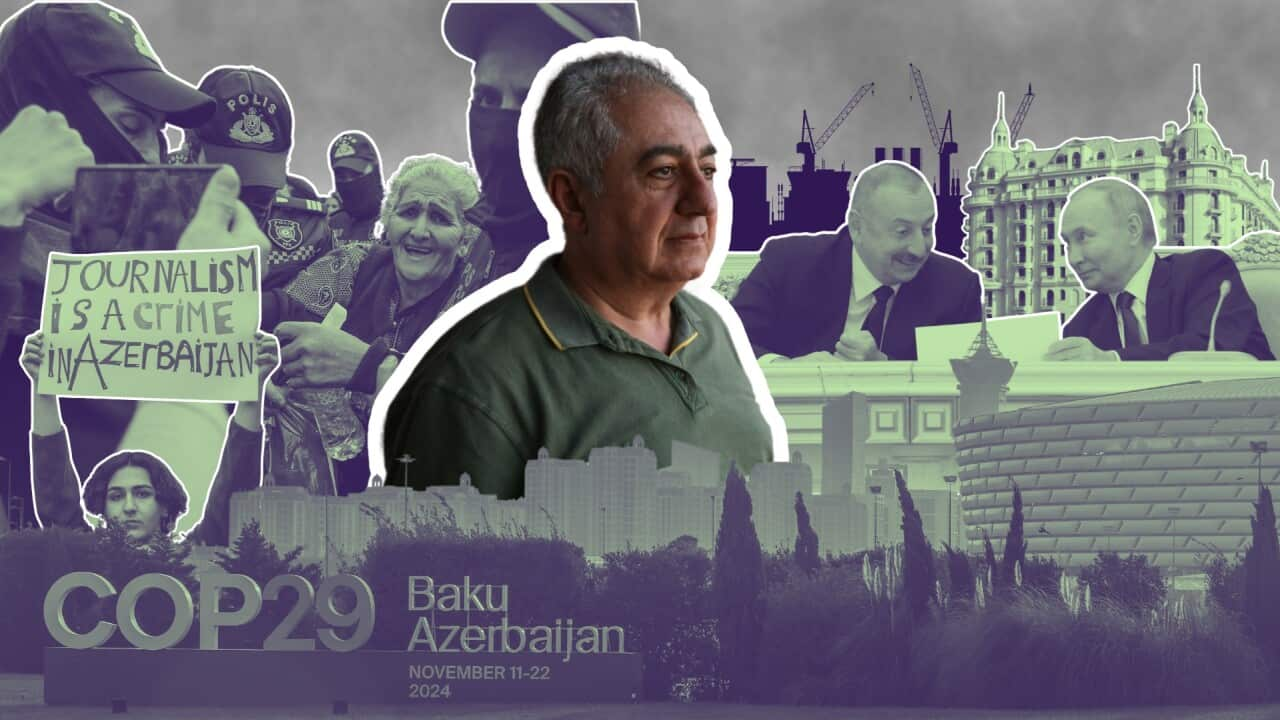

This Sunday, November 17, will mark exactly seven years since the into the protection & detention of children in the NT handed down its final report.

It recommended raising the age of criminal responsibility, a paradigm shift in youth justice to increase diversion and therapeutic approaches and increasing engagement with Aboriginal organisations in child protection, youth justice and detention.