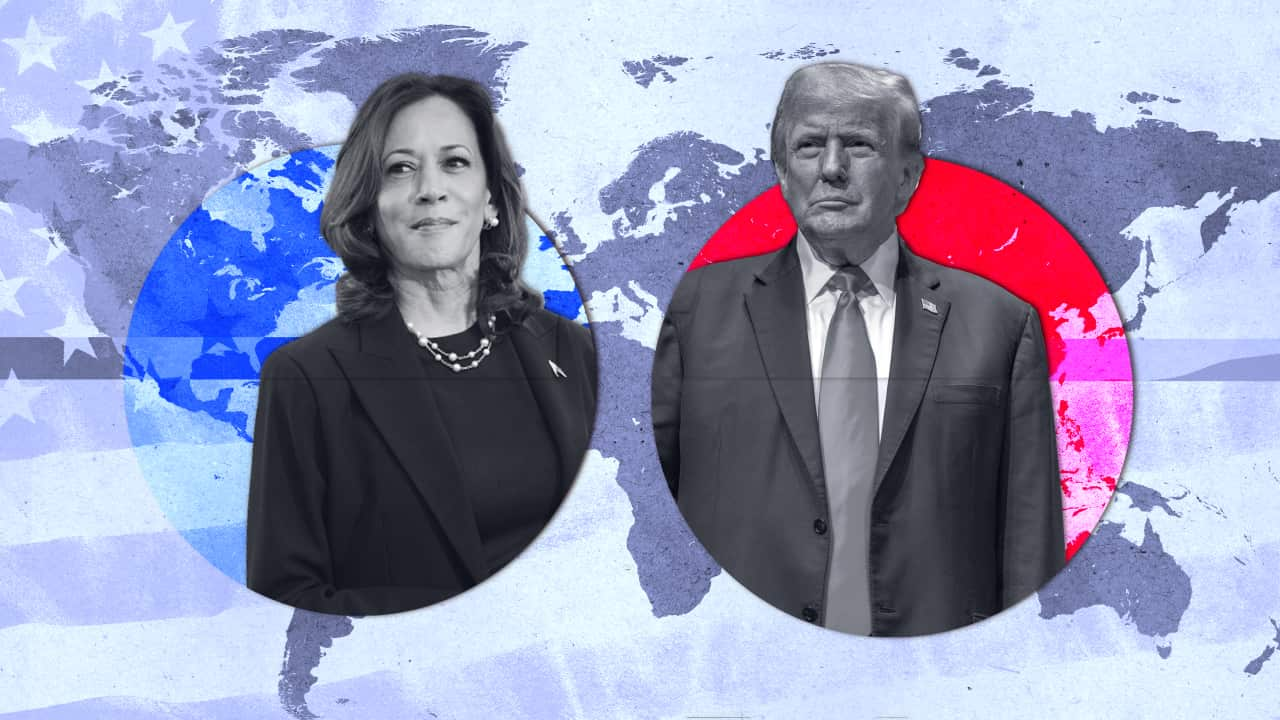

When voters in the United States head to the polls next week, they’ll not only be holding the fate of their nation in their hands — but arguably that of the world.

The presidential election comes at a globally tumultuous time, with conflict raging in the Middle East, a war in Ukraine, and China’s rising power challenging the US’ influence in the Asia-Pacific region.

How these geopolitical issues continue to play out could be influenced by whether or is elected the next US president.

“Whether we like it or not, the world really revolves around what happens in the United States,” Emma Shortis, a senior researcher in international and security affairs at public policy think-tank The Australia Institute, told SBS News.

“It’s by far the most important economy, the most important military in the world, and so much of the fate of the world, I think, is tied to what happens in the United States.”

Concerns over ‘democratic instability’

The US has long considered itself a beacon of democracy and, since the end of the Cold War in 1991, the last remaining superpower.

But Shortis said over the past decade, concerns about the “enormous amount of influence” the US has over the rest of the world have been increasing.

“Historically, it was seen as an upholder of what’s often described as ‘the international rules-based order’, but particularly when itand elsewhere, I think there have been some genuine concerns raised about the commitment of the United States to that … and to international law,” she said.

Combined with “democratic instability” in the US, many of that nation’s allies are rightly worried about what the future may hold, Shortis said.

“It’s why we are all watching this so closely and why I think there are really real concerns about what happens, particularly in the aftermath of the election, depending on how close it is and how bad that instability gets.”

Ian Parmeter, a research scholar at the Australian National University’s Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies, agreed that the result of this election and how it’s handled could pose a threat to democracy around the world.

“It clearly was not a good look for democracy when Trump refused to accept the outcome of the 2020 election and invaded the Capitol building,” he told SBS News.

“If Trump again contests the outcome, that will be a bad look for democracy, and countries that are only quasi-democracies at this stage will certainly not be encouraged to continue with democracy if they see the world’s leading democracy behaving in a way like that.”

US policy on the Hamas-Israel war

The US and Israel have been close allies since the Jewish state was established in 1948.

Following attack last year in which more than 1,200 people were killed and about 250 hostages taken, according to the Israeli government, the Biden administration has repeatedly reaffirmed its support for .

The US has spent at least US$17.9 billion ($27 billion) on military aid to Israel since October 7, according to Brown University’s .

Israel’s subsequent bombardment of Gaza has killed almost 43,000 people, according to Gaza’s health ministry. The attacks have also damaged or destroyed most of the coastal enclave’s buildings and displaced around 90 per cent of its population.

Early in Harris’ presidential campaign, there had been hope among some progressives and “moderate American support for Israel”, Shortis said.

“But as her candidacy has progressed, it’s become clear that she is maintaining the line with the Biden administration, has expressed firm support for Israel, and has continued to characterise Iran as enemy number one for the United States,” she said.

Whether that stance could change post-election would likely depend on how much pressure Harris faces from progressive Democrats, as well as the make-up of her cabinet, Shortis said.

“In contrast to the progressive pressure coming from the grassroots, there’s also been suggestions that Harris would appoint a Republican to her cabinet and may even have a Republican as secretary of state,” she said.

Parmeter said Donald Trump would be “a lot more pro-Israeli”.

“Trump is likely to give a much freer rein to to do what he needs to win the war,” he said.

“I think Trump would go along with Israel’s need to keep troops in Gaza; Netanyahu’s made very clear that he would insist on that.”

Parmeter said Trump’s support would likely extend to Israel’s objectives in Lebanon, where long-standing hostilities with Lebanese militant group Hezbollah , along with Iran, earlier this month.

“But by the same token, I think Trump will probably want the war to be finished as soon as possible,” he said.

Shortis argued it was difficult to say “with certainty” what Trump’s stance on the Middle East would be, noting his policy positions “often depend on who he spoke to last”.

“Exactly what a Trump administration might do, where the power might fall in that administration between the positions of people like the vice president, and others who are opposed to American support of war anywhere, I think is yet to become clear,” she said.

US policy on Ukraine

Where Ukraine’s concerned, there’s “a lot riding on this election”, Parmeter said.

The Biden administration has provided Ukraine with more than US$64.1 billion ($97.5 billion) in military aid since Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022.

Shortis and Parmeter said as president, Harris would try to maintain support for Ukraine like Biden has — but her success is ultimately dependent on how many Democrats are in Congress. All 435 seats in the House of Representatives and 34 in the Senate are up for grabs on 5 November.

“A lot of funding and support for Ukraine has been held up in Congress by those far-right Republicans who are opposed to American support for Ukraine, which is driven by an ideological alignment with Putin’s Russia,” Shortis said.

Parmeter noted that during , Russia was able to make “significant advances” in eastern Ukraine.

“If both the House of Representatives and the Senate end up being in Republican hands, there could be a lot more difficulty for the Harris administration to maintain that policy,” he said.

“They would certainly have to work out some way of working with the Republican-controlled Congress.”

Trump, meanwhile, has made it “abundantly clear” that as president, he wouldn’t continue the US’ support of Ukraine, Shortis said.

He’s also claimed he’d be able to .

Parmeter said that might be the case — but only in a way that would be “very bad news” for Ukraine.

“I think unfortunately it could be possible for him (Trump) to finish it pretty well on day one simply by saying that there won’t be any more American funding for the Ukrainian war effort,” he said.

“I think even if Trump can’t end the war on day one, he probably will aim to end it sometime fairly soon after he gets into office.”

US policy on China

The US’ treatment of China is one of “very few” foreign policy areas of bipartisan agreement, Shortis said.

In 2018 during Trump’s first presidency, he imposed a 25 per cent tariff on a raft of Chinese imports to the US, triggering .

Shortis said the use of “pretty aggressive economic tactics” to try to rein in China’s rising influence had continued under Biden, pointing to the tariffs his administration placed on imports like electric vehicles.

“We’ve also seen, I think, the Biden administration using the Pacific as a staging ground, really, for great power competition, and seeing much of the Pacific as kind of pawns in a security game with China,” she said.

Shortis said while that would likely continue if Harris was elected, there was potential for the US to “rethink and reshape” its approach in the region.

“I think there’d be more opportunity for the Pacific to advocate for a change in that stance, and to advocate for more of a focus — as the Biden administration initially did — on commitments to climate action and nuclear non-proliferation,” she said.

Under Trump, Parmeter said US tariffs on imported goods would likely become even “more extreme” — and not just for China.

“He has said he would be looking at 10 per cent, across the board tariffs on all countries — and that would be a worry to Australia — but also a 60 per cent tariff to start with on all Chinese goods, and then looking at other possibilities beyond that,” he said.

“All of this may go to the World Trade Organization and it may well be that there’d be international legal action against that, but just how the relationship with China develops will be very important.”

Shortis suggested the “belligerent promises” Trump has made about China may not even come to fruition.

“Trump is unpredictable in that a lot of his rhetoric around trade is particularly aggressive and will be incredibly destabilising to not only the US economy, but the global economy more broadly – and so that is of great concern,” she said.

“But we also know, of course, that , and he may see a political opportunity in pursuing a ‘deal’ with China.”

Whether any kind of deal would extend to the US supporting is also up in the air.

Parmeter noted the relationship with China would be “extremely important over the next four years … for either side of US politics.”

Additional reporting by Tanya Dendrinos

Want more politics? You can stream poignant political documentaries in the and keep up with daily news bulletins in the SBS On Demand US Election Hub.

Stay up to date with the US Election and more with the .